Mr. Meier puts the newspaper aside. “Chicago,” he says. “A city where milk trucks run over children, says Brecht. Now black helicopters are flying overhead.”

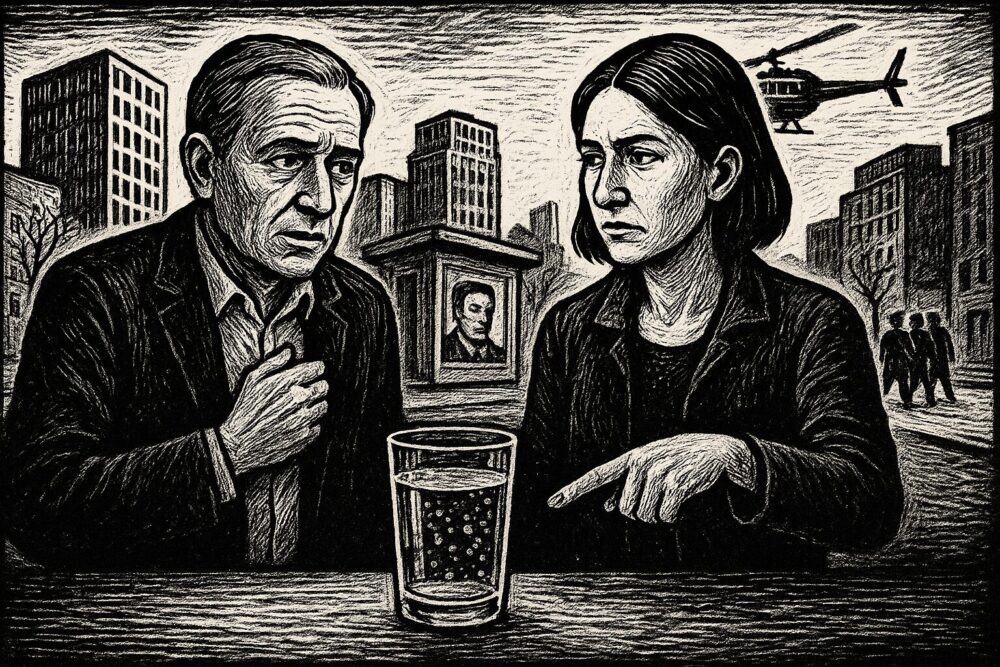

Ms. Özgül remains silent, fills two glasses with water. She slides one across the table. “Imagine this glass is Chicago. Every sparkle in it — an abduction. Every bubble — tear gas.” She taps the glass. “They say it’s about law. But law is when a judge calls the violence shocking to the conscience — and it still goes on.”

At the kiosk hangs a photo of Pastor Black, his forehead marked with pepper rounds. “They’re shooting at prayers,” Mr. Meier whispers.

“No,” Ms. Özgül corrects him. “They’re shooting at those who dare to call their actions by their name. A prayer is dangerous when it’s louder than their lies.”

They walk past the playground. A girl is drawing chalk pictures: helicopters above her house.

“See?” says Ms. Özgül. “The children already learn what danger means. Not cars, not strangers — men without faces dragging people from their beds.”

In the evening they watch the King of the USA on TV. “We bring order!” he bellows.

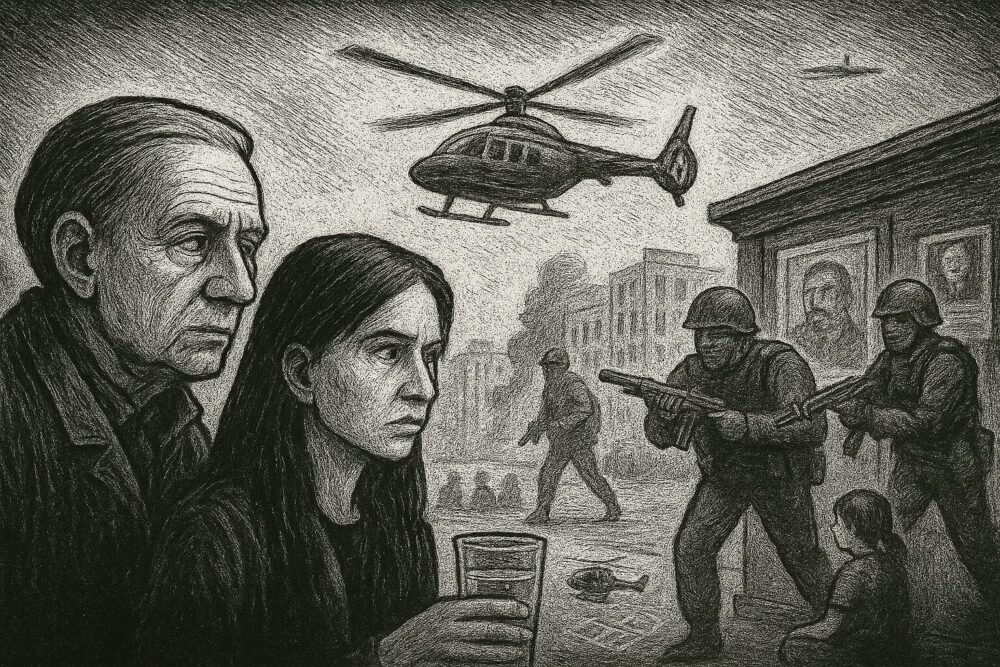

Ms. Özgül mutes the sound. “Order is when fear sets the alarm clock. When neighbors warn with their horns instead of greeting each other.” She opens the window. “Hear that buzzing? Not bees. Black Hawks.”

That night Mr. Meier dreams of a city where everyone wears a whistle. They don’t blow it out of joy, but as a warning: Here! Now! Don’t come outside!

The next day they meet a teacher on a bench. She is trembling. “They took Diana. In front of the children. Now we hide the little ones in the cupboards.”

“Why?” asks Mr. Meier.

“Because cupboards don’t have front doors you can kick in,” says Ms. Özgül bitterly.

She points at graffiti on a wall: “ICIRR Hotline — save this number!”

“This is the new ABC,” she says. “Not arithmetic, not reading — survival. How do you film an assault? How do you recognize a real warrant? How do you refuse to open the door without getting shot?”

Suddenly a black van stops. Men in uniform jump out, drag a construction worker away. His lunchbox remains on the sidewalk.

“Quick!” cries Ms. Özgül, pulling Mr. Meier aside. “You don’t want to end up in a cell with one hundred and fifty people, do you? No toilet. No lawyer.”

Mr. Meier breathes heavily. “And the voters? Seventy-seven million…”

“…voted for the king who promised to do this. The indifferent now reap what they sowed: a city pulsing like a wound.”

They pass a comedy club. A man sweeps up glass shards. “Yesterday they laughed here,” he says. “Today a mother is crying because her son was beaten while waiting for the bus.”

Ms. Özgül picks up a shard. “Chicago is like this shard. Beautiful when the sun hits it. And sharp enough to cut you.”

In front of the courthouse people are protesting with signs: “Ellis sees the truth — Bovino lies!”

“One judge against an army,” Mr. Meier murmurs.

“No,” says Ms. Özgül. “A spark against the darkness. Maybe it goes out. Maybe it ignites something.”

They buy the teacher a coffee. “What will you do now?” asks Mr. Meier.

“What we always do,” she answers. “Keep teaching. The children are learning what courage is: hanging the whistle around their necks and going outside anyway.”

On the way home someone whistles. A long, shrill sound. Ms. Özgül stops. “Hear that? That’s Chicago. Not the sirens. The whistles. The voices of those who refuse to be invisible.”

Somewhere an agent laughs. Somewhere a child cries. And in between — very softly — the click of a phone camera capturing what the powerful want to erase.

“And us?” asks Mr. Meier.

“We keep telling the story,” she says. “Until even the last person understands: What’s happening in Chicago will come to us tomorrow. If we stay silent.”

She takes his hand. Their hands tremble. But they keep walking.